Do support services, such as the NOVA writing center, shown here, help produce greater outcomes inside the developmental/ESL English classroom? Williams would argue that, with the right tutor strategies, they do.

In considering issues related to developmental/ESL English at the community college, one important goal of teachers and the school alike is providing adequate support to make students successful in their courses. In looking at what support services are available to improve outcomes for developmental/ESL English students, writing centers are an important resource. Jessica Williams in “Undergraduate Second Language Writers in the Writing Center” examines the historical problems for both teachers and writing centers for addressing ESL students and what might be done to support greater outcomes for these students in need.

Williams notes that while teachers have been using writing centers as a place to help “fix” or “improve” ESL writing student outcomes, most writing center tutors succeed in helping writers with their writing issues, but fail to help them with language issues. “For the latter, some tutors may refer second language writers to handbooks, which generally contain explanations of troublesome grammatical forms and sentence-level exercises” which are often “frustratingly ineffective” (75). However, Williams believes that the research and particular methods can make the writing center effective for second-language writers and outlines methods for improving student outcomes.

First, tutors in the writing center can assist students by teaching students concepts systematically. This “system learning” is for when tutors and students are able to see grammatical or language patterns throughout writing. For example, when a student can recognize that the “regular past tense marking with ed” is a pattern, they can project that knowledge “onto new forms” (78-9). Applied linguists generally agree that such teaching is possible on the part of the tutor (78), as long as the the tutor knows the grammar rules himself (79).

Second, the tutors should act more as a peer and guide the second-language writer to negotiate the writing with them. ESL students prefer a more “directive” session with a tutor, in which the tutor behaves “as higher-standard interlocutors” with more dominant behavior. Research has shown that being more directive might be helpful for ESL writers (80), yet for the best results, negotiation, in which the learner participates actively with the tutor to facilitate comprehension and possible revisions will lead to the greatest outcomes (81-2). Texts that are negotiated with tutors tend to receive the most revision (83).

Finally, Williams addresses the sociocultural approach to helping ESL English students. The zone of proximal development is Vygotsky’s theory on learning, in which stretching current knowledge in interactions with novices or peers helps students internalize new knowledge (84). In the writing center, this can be achieved by asking the writing center tutor to act as an “interlocutor” in which they control the “flow of discourse, but there is a moderate mutuality” and active encouragement of the novice to contribute (85). These three methods together can result in strong outcomes and gains for the ESL writer in their writing classroom.

The methods that Williams brought up as the ways to support ESL writers reminded me of Richard Fulkerson’s “Four Philosophies of Composition.” Within this approach, I can see how at least three of his philosophies can be accounted for in these methods. The formalist approach, which judges “good writing as correct writing” and “readability” (344) can be seen in Williams’ notion of system learning – students can be taught particular forms to make their writing more readable. I can see the philosophy of expressionism, which focuses on students as self-directed and teachers as non-directive (345) in Williams’ suggesting that students have some directive aspects in their writing. Finally, I see the mimetic approach, which says there is a connection between good thinking and good writing (345) when Williams points out that one of the biggest challenges for ESL writers is in reading comprehension. A struggle with comprehension of required college texts “can pose a tremendous challenge for these second language writers” (77). What is interesting is that Fulkerson acknowledges how problematic it is to use multiple approaches at once, or to use one approach and grade based upon another (346). However, writing tutors might escape these issues because they work one-on-one with the writer and they have no stake in the grading of the work. Therefore, it seems possible that support services like writing centers can help students simply based on their ability to perform multiple philosophies or functions without having to assess the work. Such a theory could explain one reason why students who use the writing center have greater outcomes in their classes than students who do not.

My own experiences working with students in class and one-on-one might speak to the possibility of the successful multitasking writing tutor. For example, when I teach my developmental composition course I do not generally teach grammar usage. As is widely accepted, particularly after Patricia Hartwell’s definitive piece “Grammar, Grammars, and the Teaching of Grammar,” explicit teaching of forms is not particularly productive. However, when students are one-on-one with me and I can see small patterns of errors in their writing, discussing these issues, as a writing tutor would do, becomes more practical and useful. I also generally find that ESL students struggle the most with reading comprehension of any deficiencies they may have, and this is a major inhibitor to clear and understandable writing. I encourage them to read frequently (both for and outside of class), ask questions, and talk with their peers. Helping with basic comprehension of a given task or writing instantly makes their job easier. Finally, I see the value both in letting students making directives for their writing while also letting me guide them a bit – a middle ground approach is always better than allowing only them to talk or only me to talk when we conference about their writing. In addition, so much more is accomplished when I am facing only one student rather than 25 or more.

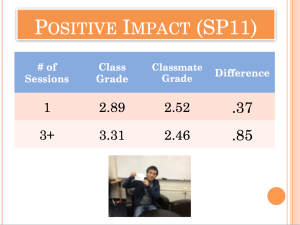

At NOVA’s writing center, the results of such benefits are definitive. The writing center has done their own studies showing the benefits of their work. Below, you can see that students who visit the writing center do better in their courses than students who do not. These support services, therefore, are crucial to continued ESL in the English classroom success.

These statistics, from NOVA’s writing center program assessment in spring 2011, show that writing centers do make a difference based on the number of times the student goes. This supports the idea that with good tutoring techniques, students, ESL or not, can improve their writing.

Works Cited

Fulkerson, Richard. “Four Philosophies of Composition.” College Composition and Communication 30.4 (1979): 343-348. Print.

Hartwell, Patricia. “Grammar, Grammars, and the Teaching of Grammar.” College English 47.2 (1985): 105-127. Print.

Williams, Jessica. “Undergraduate Second Language Writers in the Writing Center.” Journal of Basic Writing 21.2 (2002): 73-91. Print.