In this article, Bruce Horner and John Trimbur follow the history of composition and the developmental shifts from seeing second languages as an integral part of rhetoric and composition in the college to the college as a segregated space in which ESL students are seen as lesser in the eyes of the academy.

Horner and Trimbur take us on a historical journey, which starts when Greek and Latin study were an integral part of the rhetoric curriculum until the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. At that time, a shift began in which languages such as French, German, and Spanish became reading courses intended to study a national literature or culture, and “English alone was assigned the task of writing instruction” (595-6). By the time of the Civil War, major universities like Harvard and MIT had “dispensed with” language learning as a graduation requirement (598), and languages such as Greek and Latin were seen as a dull and mechanical translation exercise (599). In 1890, Adams Sherman Hill and the Harvard Committee on Composition and Rhetoric created the first year writing course at Harvard, which was entirely focused on the study of English writing (598). While some in the discipline still advocated for language study, such as Theodore W. Hunt (who hoped to divide language and literature curriculum between several major languages), this advice went unheeded in favor of English exceptionalism (602).

By the start of the twentieth century, there was little need seen to acquire multiple languages, as Americans were not forced by geographical location (unlike Europeans) to do so. This monolingualism represented the “era’s patrician fears of race mixing, mongrelization, and a loss of vigor among the better classes” (606-8). Horner and Trimbur note, then, that this movement towards monolingualism, or the accepting of only one language, was a response towards a fear of foreigners and other cultures, also known as xenophobia, which has continued into the 21st century (608). This has spilled into the college and the composition classroom; “Basic writers have commonly been described as immigrants or foreigners to the academy, those whose right to be there is suspect and whose presence is often seen as a threat to the culture, economy, and physical environment of the academy” (609). This xenophobia is further fueled in the academy by students who frequently move back and forth between the U.S. and their home countries and position themselves as “between worlds” (612).

Foreign students also take placement exams and these become “evidence of their language use as a whole, which is assumed to be fixed and uniform,” which means they are further positioned as outsiders in the academy, where their writing is seen as static rather than “shifting” (614). Teachers may also lump foreign students together into categories that may or may not exist, such as “all Chinese students make X mistake” or “all Arabic students write with flowery dialogue.” This is also, the authors state, troubling, “regressive, and limiting” (619). Finally, they note that composition teachers must examine their own pedagogy and assumptions about an English-only curriculum and stop identifying students by their language and language ability, even if it seems natural to do so (622).

_____________________________________________________________________________________

This really resonated for me particularly after reading Matsuda for my first PAB entry. This gave a somewhat older history of the field and showed how English-only became the model of choice based both on remediation, which is what Matsuda suggested, but also xenophobia and a fear of foreigners. I’m inclined to believe that the truth lies in both of these answers. Both pieces come to similar conclusions, however, which is that colleges must be inclusive of all types of students and be open to the variety of language and culture that they can bring into the class.

This piece reminded me of our class discussion on Fulkerson’s 1979 article discussing the four philosophies of composition. Under what Fulkerson outlines, the history of the field might spring from a formalist interpretation of good writing, in which good writing is primarily free of errors in spelling and grammar (344). The English-only movement would be primarily seen as a way to keep out of the academy those who could not meet a formalist model of composing. What is interesting, however, is that rhetorical is now the dominant model. The rhetorical model says “[G]ood writing is writing adapted to achieve the desired effect on the desired audience” (346). However, while this is the dominant model, the English-only movement struggles to allow other forms of argumentation other than the “American” style to dominate. Interestingly, because teachers here generally seem to favor a particular style of argument, it might seem that the rhetorical model might also be a source of exclusion for second-language speakers. Fulkerson might argue that teachers need to be careful how they assign and assess writing for second-language learners, as they must be aware of their biases and how they are judging the work.

This work also brings me back again to questions that I had with Matsuda about what is the best tactic for allowing students into particular composition classrooms. While these authors certainly acknowledge that English is here to stay and will always be the dominant language in the college classroom, what, again, is the solution to the “testing” dilemma that they bring up? Do we test students and pigeonhole them as being at a certain “level” or having a certain “ability,” or do we allow them to do what feels comfortable? As a teacher of developmental English, I often get a range of students (as does any teacher); some students really do not need developmental English and others I am surprised they are in credit-bearing English. I certainly see that their thoughts might be as strong as their higher-level classmates, but at what point do we wipe away the testing system completely and devise a new system to reduce discrimination? This is a conversation NOVA is having and more solutions need to be found.

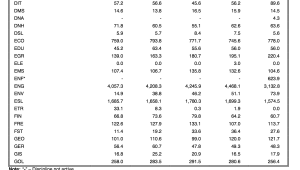

Because I frequently teach developmental English (and am also a former ESL teacher), this might be a good place for dissertation work for me down the line as I am truly passionate about helping students get up to speed with their English work, as it is frequently the thing that holds them back from completing degree programs. In fact, I have been told by several students that they consider transferring to a for-profit college because they can skip the ESL and developmental sequence all together. This is a great disadvantage to students. I think we must somehow meet in the middle – unburden students yet offer a high-quality education. Below, I have shown two pieces of data from NOVA that highlight how many English classes (developmental, ESL, and otherwise) that the average NOVA student is taking. While good for business, we need to address how many students are in and are staying in our classes repeatedly and how this is affecting their chances for future success.

[Here is one example – this is often a typical sequence for foreign students to go through – taking many, many non-credit bearing courses before reaching developmental English. Are we helping or hindering this student from success?]

[Here is a second example – this comes from the 2013 NOVA factbook. Look how many students are taking English, developmental English, and ESL. Each column represents one year. They make the other courses at NOVA look paltry by comparison.]

Works Cited

Fulkerson, Richard. “Four Philosophies of Composition.” College Composition and Communication 30.4 (1979): 343-348. Print.

Horner, Bruce and John Trimbur. “English Only and U.S. Composition.” College Composition and Communication 53.4 (2002): 594-630. Print.