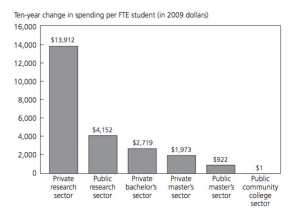

According to this article from Slate.com, between 2003-2013, community colleges only received an extra $1 per full time student. Community colleges have had to cut back, which leads to shortcuts such as placement testing over more proven multi-assessment measures to place students. Without increased funding, are community colleges doomed to continue misplacing and discriminating against English Language Learners?

The study of ESL/developmental English has one important question that has been asked now for close to twenty-five years. That question is: do placement tests work for placing students into developmental English, and if they don’t work, what can replace them to accurately place students in need into developmental English classes without placing everyone or no one in them?

The history of this question begins with the placement tests themselves. As I have mentioned in other posts, Harvard was the first school to pioneer the placement exam. These tests was meant to contain students who did not have “correct” English in separate courses from those students who did, suggesting that “language differences [could] be effectively removed from mainstream composition courses.” With an influx of immigrant students coming to study in the U.S. during the second part of the nineteenth century, most other schools began requiring language exams as well (Kei Matsuda 641-42). This practice continued on without question, according to Deborah Crusan, until approximately thirty-five years ago. Crusan notes that indirect measures of assessment, such as the Compass or ACCUPLACER, were used by schools because they resulted in less inter-reader unreliability that was traditionally associated with scoring of placement essays by independent raters. By the 1970s, however, academia started criticising such tests on the grounds that writing could not be assessed by a computer, and by the 1990s, the idea that writing can be tested indirectly “have not only been defeated but also chased from the battlefield” (18).

Despite the fact that the question of the accuracy of these exams seems to have been debunked, according to Hassel and Baird Giordano, over 92 percent of community colleges still use some form of placement exams. 62 percent use the ACCUPLACER and 42 percent use Compass; other schools use some combination of the two (30). These tests are still very much alive and being used although research by the TYCA Council shows that these tests have “severe error rates,’ misplacing approximately 3 out of every 10 students” (233). Worse yet, when students are placed into courses based on these standardized placement scores, it is found that their outcome on the exam is “weakly correlated with success in college-level courses,” resulting in students placed in courses for which they are “underprepared or over prepared” (Hodra, Jagger, and Karp). At Hassel and Baird Giordano’s community college, the retake rate of classes in which students are placed ends up being 20-30 percent for first semester composition, showing the extreme proportion of students testing into a class for which they are unprepared (34).

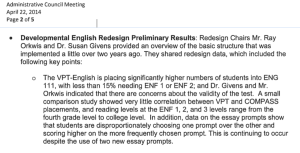

There has been a massive amount of research done on approaches to fix this problem. Typically these approaches involve using multiple methods for assessing student writing or re-considering how we use the placement exam. For example, Hassel and Baird Giordanao found greater student placement and success using a multi-pronged approach. This approach includes looking at ACT or SAT scores (37); asking students to complete a writing sample, with an assessment corresponding to the writing program’s learning outcomes (39); examining high school curriculum and grades (41); and student self-assessment for college English readiness (41-42). On the other hand, Hodra, Jaggers, and Karp suggest revamping the way we assess college placement exams by improving college placement accuracy. These methods include: aligning standards of college readiness with expectations of college-level coursework; using multiple measures of college readiness as part of the placement process; and preparing students for placement exams (6). They also recommend standardizing assessment and placement policies across an entire state’s community colleges, such as what Virginia has done with the Virginia Placement Test (VPT) (19).

Unfortunately, even redesigns of placement tests that become statewide are not always a good solution. These notes from a NOVA Administrative Council Meeting last April show that despite efforts to create a statewide standardized test, students were less successful in English than ever. Does this add to the data that standardized tests just don’t work?

These outcomes lead us to a final question that still remains: if we know how to “fix” the problem, why are colleges unable to implement the solution? This comes down to money. One administrator said that multiple measures sound “wonderful, but I cannot think about what measures could be implemented that would be practical, that you would have the personnel to implement” (Hodra, Jaggers, and Karp 23). Until we find a solution to the problem of funding and staffing, the placement test will remain.

If we acknowledge that the money for such a revamp at most big schools, such as NOVA (which has over 70,000 students), is not going to appear now (or likely ever), what other potential solutions remain? In thinking about such solutions, I began to consider the reading on the “Pedagogy of Multiliteracies” by the New London Group that we read for class. In this manifesto, the writers note that current literacy pedagogy is “restricted to formalized, monolingual, monocultural, and rule-governed forms of language” (61). The demands of the “new world,” however, require that teachers prepare students that can navigate and “negotiate regional, ethnic, or class-based dialects” as a way to reduce the “catastrophic conflicts about identities and spaces that now seem ever ready to flare up” (68). This means that colleges must focus on increasing diversity and connectedness between students and their many ways of speaking. To me, this acceptance of diversity of person and language inherently seems to be part of the solution. In recognizing that all students should have their own language, we start to break down the separation and therefore the tests that misplace and malign students.

If we are to subscribe to the “Pedagogy of Multiliteracies” but find that we cannot afford to include multiple measures into our assessment of students, Peter Adams might come closest to having a good solution that brings together help for ESL/developmental students, does away with the placement exam as a site of discrimination, and make mainstream students more aware and respectful of multiliteracies. Adams suggests that schools should still have students take placement exams, yet if a student tested into developmental, they have the option to take mainstream English. The idea is that the weaker writers could be pulled up by the stronger writers and see good role models. In addition, developmental writers take an extra three-hour companion course after the regular course, which has about eight students, leading to an intimate space for students to ask questions and learn (56-57). This model was found to be very successful at Adams’ Community College of Baltimore County; students held each other accountable, were motivated by being part of the “real” college (60). They also avoided falling through the cracks as they passed their developmental course but never registered for English 101, which is a common problem in many community colleges (64).

I truly believe that such a method as Adams suggests is a great idea for NOVA. I teach developmental/ESL English courses in which all of our students are developmental, with no “regular” students. In the “regular” sections of first-semester composition I have students who are well-prepared as well as students who passed the newly deployed VPT exam, which has resulted in more students than ever placing into regular first-semester composition. From my experience, these weaker students in regular composition tend to be more resilient – they are perhaps pulled up by the stronger students, or maybe they know if they can pass this class they are done with half of their English requirement. I compare this to my developmental students, of which I will lose approximately 30-40 percent each semester to failure, attendance issues, disappearance, or language struggles. With the approach Adams suggests, I believe that NOVA could help pull our developmental students up to a higher level of achievement and we could also empower them to continue on with their studies. This would cost much less than a multi-measures approach proposed by those seeking to fully do away with placement exams. I believe this solution would be the best way to “meet in the middle” and solve both the financial and discriminatory practices that are frequently related to placement exams.

Works Cited

Adams, Peter, et al. “The Accelerated Learning Program:Throwing Open The Gates.” Journal Of Basic Writing 28.2 (2009): 50-69. Print.

Crusan, Deborah. “An Assessment of ESL Writing Placement Assessment.” Assessing Writing 8 (2002): 17-30. Print.

Hassel, Holly, and Joanne Baird Giordano. “First-Year Composition Placement at Open-Admission, Two-Year Campuses: Changing Campus Culture, Institutional Practice, and Student Success.” Open Words: Access and English Studies 5.2 (2011): 29–59. Web.

Hodara, Michelle, Shanna Smith Jaggars, and Melinda Mechur Karp. “Improving Developmental Education Assessment and Placement: Lessons From Community Colleges across the Country.” Community College Research Center. Teachers College, Columbia U CCRC Working Paper no. 51. Nov. 2012. Web. Accessed 23 Sept. 2015.

Kei Matsuda, Paul. “The Myth of Linguistic Homogeneity in U.S. College Composition.” College English 68.6 (2006): 637-651. Print.

The New London Group. “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures.” Harvard Educational Group 66.1 (1996): 1-32. Print.

Two Year College English Association. “TYCA White Paper on Developmental Education Reforms.” TYCA Council. 2013-2014. Accessed 18 Sept. 2015.