As I sit down to tackle this final paper, it is also nearing the end of another semester of teaching composition and developmental English at my community college, NOVA. Students are frantically writing their final essays and creating final projects while I am frantically trying to grade hundreds of pages of writing before they rush off to Christmas break. Soon enough, it will be January and we will return to do it all over again: new faces, new essays, but still the same challenges.

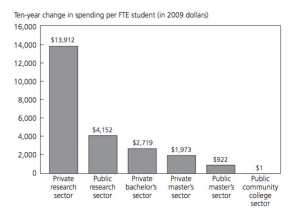

The reason I’ve taken you on this bit of a narrative journey is because over the course of this semester, in getting to think about what it means to be a scholar of developmental English, I’ve taken a look at my own practices as a composition teacher and realized that the pace at which I must teach is something that is fairly unique to the community college. As a teaching institution rather than a research institution, I find myself teaching often 125 students a semester and have recently discovered that for some community college educators, this is a light load. Ultimately, though, teaching is what I want to be doing – my path to the community college has been, perhaps, an unusual one, and I’d like to think about how I got here and where I am headed based on the path (both physically and educationally) I have taken, and why scholarship and what I have discovered in this class is suddenly so relevant.

My educational background is in both literature and writing. As an undergraduate at the University of Minnesota, I was an English major with an emphasis in creative writing. My education was still heavily lit-based, but my heart was really in my writing. I wanted to write books, particularly creative nonfiction. Unfortunately, as most of us know, this doesn’t exactly pay the bills. Nearing the end of my four years, I realized that teaching would be a great way to enter a field that I cared so much about, and that by becoming a professor, I might be able to dabble both in the world of literature and creative writing. Not ready to go back to school right away, I ended up moving to Seoul, South Korea, where I taught English as a foreign language for two years in a public elementary school. I loved the EFL population, but my heart was still in teaching adults. By the time I returned to America to pursue my master’s degree, I was ready to make that dream a reality. I attended Marymount University in Arlington, Virginia while teaching English as a second language to adults. Though my teaching load was extremely heavy at that time – I taught five hours of new material each day, Monday through Thursday, I became passionate about the decision I’d made to teach adults and I really enjoyed the work I was doing in ESL – helping young people to learn a new language because of their goal to get a college degree was extremely rewarding.

It was also at this time that I was exposed to composition as a field at Marymount and I began to consider community college as a good option for me. My work at the ESL school made me realize I wanted to teach. I am a people-person by nature and couldn’t see myself slaving over a desk in research when my heart was in the classroom. When I applied for teaching position at NOVA and was hired full time on my first attempt, imposter syndrome reared its ugly head. I questioned myself down to my core about my ability to do the job I was tasked to do: “why would anyone trust me to talk to students about their writing, and why would anyone believe I was qualified to give them a grade that could affect their future?”

Applying for the PhD program at ODU was in part an effort to silence my inner critic. Since embarking on this journey, I have only alleviated the imposter syndrome a bit because I now realize, yet again, that even having learned so much this semester, how little I truly know about my own field. Yet, what I have learned in this class (aside from, of course, more knowledge about being a developmental English teacher) is how little there really is on community college scholarship in tackling the many issues of developmental English; and I have therefore realized, despite what I’ve written all semester, I am most interested in situating myself as a scholar on the border of developmental English and community college issues. Right now, I have my “dream job” and it would be easy to abandon further higher education. I could work through my imposter syndrome in other ways – through improving my teaching methodologies, for example. But I now consider that there is so little scholarship on community college as an autonomous unit because we are so heavily involved in our 125 students each semester – we often struggle to find time to squeeze the “scholar” part in. I now believe that my place to contribute is to bring forward that hidden “scholar,” make just a little extra room for it, and to contribute to the field of developmental English at the community college. I feel I have found my place.

Because I have written so much this semester on being a scholar of developmental English, I want to touch upon what I have already written, and what it means to be a scholar of that field, yet I want to continually reflect upon what these things mean as a teacher at a community college and what I might consider about being a scholar sitting at the intersection of the fields of developmental composition and community college scholarship going forward.

In my first paper, I wrote about the history of the field, drawing particularly heavily on Paul Kei Matsuda, who you may recognize as someone I go back to again and again. Reading him as a master’s student was, as someone interested in ESL issues, a turning point in thinking about what it means to be a scholar of developmental English. In my history paper I note:

Harvard, from which the first year writing course began, also pioneered the writing course as a place of containment for “correct” English, though by the second part of the nineteenth century, with an influx of immigrant students coming to study at research universities, it was not only Harvard that required placement exams. Many other schools required language exams that were the site of linguistic containment and discrimination (Kei Matsuda 641-42), which was an attempt to make it appear that “language differences can be effectively removed from mainstream composition courses” (642). Second-language speakers, from Ivy League schools, to research universities, to historically black colleges and universities were sending many students, particularly Asian students, to remedial language schools until they were able to return to the school to study (644).

The idea of “correcting” or “fixing” linguistic differences is knowledge that is absolutely necessary for a scholar of developmental English. Seeing that the history of the field was one borne out of problem-solving and linguistic prejudice rather than a course meant to improve critical thinking and research skills is an idea that has heavily influenced me as a scholar. I continually try to challenge this mode of thinking not only in myself but also in my students who are continually asking for the “right” answers to writing problems and situation. In reflecting upon this now, sitting at the precipice of not only developmental English scholarship but also community college scholarship, I know that I can contribute here in thinking and studying more on this from a linguistics perspective – how we can challenge the current notion (as Dell Hymes wrote) about what effective communicative competence means and how we can empower the great number of community college ESL students in the classroom to move forward as thinkers less concerned with English usage and more on the power of their rhetoric and critical thought.

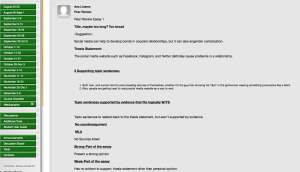

My second paper on major questions built strongly upon the ideas from my first. I challenged the notion of the placement test as an effective tool for putting students in developmental English, with the Virginia Placement Test (VPT) as a particular driving force of this question. NOVA is required to use the VPT to place students, and this test has had the unfortunate effect of placing too many students who are unprepared into credit-bearing English. This problem is now being seen across the community college system in Virginia. In my research, I discovered:

Despite the fact that the question of the accuracy of these exams seems to have been debunked, according to Hassel and Baird Giordano, over 92 percent of community colleges still use some form of placement exams. 62 percent use the ACCUPLACER and 42 percent use Compass; other schools use some combination of the two (30). These tests are still very much alive and being used although research by the TYCA Council shows that these tests have “severe error rates,’ misplacing approximately 3 out of every 10 students” (233). Worse yet, when students are placed into courses based on these standardized placement scores, it is found that their outcome on the exam is “weakly correlated with success in college-level courses,” resulting in students placed in courses for which they are “underprepared or over prepared” (Hodra, Jagger, and Karp).

As a community college scholar and one of developmental English, this professional knowledge seems essential. Realizing that we have a broken placement system that was put in place by the government says so much not only about our students’ struggles, but also what struggles we will face in a world where college is becoming ever more crucial. While I had known before this class how weakly correlated placement tests were with success, it was through my study this semester that I discovered how political it all was. What I ended up reflecting upon in this paper was a recommendation that students might test into developmental but still take regular English. Now, at the end of the semester, these musings seem basic and don’t really focus on how to handle this challenge at the community college. Contributions I could make to actually work towards solving such a problem instead of looking at quick fixes are not simple, but working on data collection about the results of these tests and moving those forward through publications might help shed light on how the VPT is working, allowing for greater dialogue on how to resolve this complex issue.

The state seal of Virginia – is the government becoming a tyrannical force at the community college?

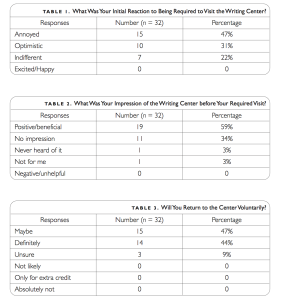

In my third paper, I went on a totally different route in thinking about writing centers as an object of study for developmental English. I considered how support services such as the writing center might support the development of these writers on an individual level. The research showed that writing centers were extremely useful in helping students improve, not only from a usage level, but generally in thinking about the problem-solving tasks of writing (Dinitz and Howe; Jones). While discovering the literature on their usefulness was a wonderful discovery, this paper is also where I first dove into the problems related specifically to the community college. I noted:

…the writing center at NOVA is quite understaffed for a school of our size. While the writing center claims that students need only make appointments two weeks in advance, my students tell me that they cannot book even four weeks out because the center is full. When the advice of many of the writers I surveyed mentioned that requiring students to use the writing center is actually quite useful, how, when my students can’t even book individual appointments, can I get them all to see a tutor?

I have since discovered that our writing center has been further reduced due to financial cutbacks. These cutbacks are something that I have had growing concern about throughout this semester and are now affecting my students. While perhaps knowing about the efficacy of writing centers and other support services is not imperative for a scholar of developmental English, it certainly is for a community college scholar. Where I can go from here and contribute to the field is a great concern of mine. I see no entry point yet, but know that if this problem is not solved, my discipline and my job are in great peril.

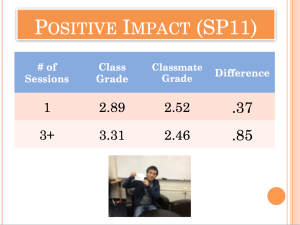

Finally, in my fourth paper I talked about the theories and methods of cooperative and collaborative learning. I liked this theory and method because it is more of a new technique and one that came after the “social turn” in the field. In particular, I think it is importantly connected to the problems that developmental English students often face, and, as the research shows, is a potential solution to major gaps in learning that most developmental students have. In my research I discovered:

…studies have shown that cooperative learning allows members to pool knowledge, “share cognitive load among members,” and check each other’s thinking for errors (Klein and Lealock 134). This leads to texts that are more accurate linguistically and writing that contains more new ideas as members learn and refine new ideas (140-141). Jehangir’s research concurs, noting that “‘there is a growing sense that teaching and learning don’t really happen unless there is some kind of building relationship – not only between teacher and students but between teachers, students, and subject’” (91). Collaborative writing even has the benefit of getting “richer thinking and more voices into solo writing as well,” according to Elbow (267).

This way of thinking is hugely important to my pedagogy and practice in the classroom, but yet again, in this paper, I began to see myself as not only a scholar of developmental English but also a scholar of the community college. It struck me that when I work towards cooperative learning in my own classroom, there are always students who struggle with it, no matter what relationships I try to foster between collaborative groups. I began to note that while different learning styles are important, I thought about the varied lives that students have outside of the classroom, and that many of my students struggle with disabilities (both acknowledged and unacknowledged) that inhibit learning and cooperative work. This breakthrough made me again aware that while cooperative learning modes might be important knowledge for being a scholar of developmental English, it is the unacknowledged challenges such as students with disabilities (a burden which the community college faces at a rate of twice that of other higher educational institutions) that must now be turned towards when thinking about such methods. Again, my entry point into this conversation is tenuous, but considering how to best help students with varied disabilities in the composition classroom is something I am extremely interested in considering further on in my coursework. In fact, if I am able to further see what information is available about this topic, it might be a good entry point for dissertation work.

Students often have disabilities that can’t be seen, which affect not only their ability to do the coursework, but how they react to learning strategies in the classroom, too.

Ultimately, I have discovered a lot this semester about my field and unexpectedly realized that a potential field for study that I care deeply about is right in front of my face. This paper in particular has made me consider what Janet Emig says in her essay “Writing as a Mode of Learning”: In writing these posts, I have had a chance to play with so many ideas and have come to realize that I am passionate about composition, yes, but also the unique challenges of the community college.

Another facet of considering writing as a mode of learning has also made me acknowledge how disparate the papers I wrote this semester really are – writing centers, cooperative learning, placement tests – how does it all fit together? I believe this class has helped me realize that, as Pifer says, I might connect these papers by recognizing that as a composition scholar at a community college, where my first job is teaching, I am really more of a generalist. I’ve dipped my quill into many proverbial educational pots this semester and used writing as a way to clarify and find greater self-awareness of who I am in this field and that is OK.

Ultimately, I still know so little about the fields I am embarking on (the more I know, the more I know I want to know), but I do know that taking the approach of a generalist is a good way to start and what I believe I have done this semester. There are some things I am certain I don’t know and want to know more about – particularly the use of technology in the composition classroom – but other than that, there are so many areas of study that I am waiting and hoping to discover. As I continue my journey through my PhD, I am excited to discover new ways to contribute to these major debates as a scholar at the precipice of developmental English and the community college.

Works Cited

Dinitz, Susan, and Diane Howe. “Writing Centers and Writing-Across-the-Curriculum: An Evolving Partnership.” The Writing Center Journal 10.1 (1989): 45-53. Web.

Elbow, Peter. “Using the Collage for Collaborative Writing.” Teaching Developmental Writing. Ed. Susan Naomi Bernstein. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford-St. Martin’s, 2007. 261-268. Print.

Emig, Janet. “Writing as a Mode of Learning.” College Composition and Communication 28.2 (1977): 122-128. Print.

Hassel, Holly, and Joanne Baird Giordano. “First-Year Composition Placement at Open-Admission, Two-Year Campuses: Changing Campus Culture, Institutional Practice, and Student Success.” Open Words: Access and English Studies 5.2 (2011): 29–59. Web.

Hodara, Michelle, Shanna Smith Jaggars, and Melinda Mechur Karp. “Improving Developmental Education Assessment and Placement: Lessons From Community Colleges across the Country.” Community College Research Center. Teachers College, Columbia U CCRC Working Paper no. 51. Nov. 2012. Web. Accessed 23 Sept. 2015.

Hymes, Dell. “On Communicative Competence.” Research Planning Conference on Language and Development Among Disadvantaged Children. Yeshiva University. Frankfurt Graduate School. 7 June 1966. Address.

Jehangir, Rashne. “Cooperative learning in the multicultural classroom.” Theoretical perspectives for developmental education. Ed. J. L. Higbee, & D. B. Lundell. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, General College, Center for Research in Developmental Education and Urban Literacy, 2001. 91-99. Print.

Jones, Casey. “The Relationship Between Writing Centers and Improvement in Writing Ability: An Assessment of the Literature.” Education 122.1 (2001): 3-20. Web.

Kei Matsuda, Paul. “The Myth of Linguistic Homogeneity in U.S. College Composition.” College English 68.6 (2006): 637-651. Print.

Klein, Perry D., and Tracey L. Lealock. “Distributed Cognition as a Framework for

Understanding Writing.” Past, Present, and Future Contributions of Cognitive Writing Research to Cognitive Psychology. Ed. Virginia Wise Berninger. New York: Psychology Press Taylor and Francis Group, 2012. 133-152. Print.

Pifer, Matthew T. “On the Border: Theorizing the Generalist.” Transforming English Studies: New Voices in an Emerging Genre. Ed. Lori Ostergaard, Jeff Ludwig, and Jim Nugent. West Lafayette: Parlor Press, 2009. 179-194. Print.

Two Year College English Association. “TYCA White Paper on Developmental Education Reforms.” TYCA Council. 2013-2014. Accessed 18 Sept. 2015.