Studies show that when it comes to ESL/developmental English students utilizing support services such as the writing center, a hands-on approach is more useful than it is for native English speaking students.

One research question that is important in the world of ESL/developmental English regards the support services offered to help improve outcomes for students. Questions that are important are: what support services do colleges offer to ESL/developmental students? Are these successful in helping improve outcomes? One such generally accepted OoS in the discipline are writing centers. According to Jones, many studies have shown significantly higher grades for students who utilize writing centers (9). NOVA’s own study of writing centers (as detailed in PAB #5), writing centers are shown to significantly increase student outcomes the more frequently students visit. In addition to being shown to help students improve grades, Gordon notes that 74 percent of students who visit writing centers find them to be helpful, and 84 percent recommend other peers to visit as well (157). While students may initially feel anxiety at the prospect of visiting a writing center, because they are often spaces of “non-judgemental, collaborative assistance, these apprehensions tend to evaporate” (Jones 11). Such visits frequently lead to students improving their attitudes and self-perceptions related to their writing. Jones also notes that writing centers go beyond improving student writing, but are also a key in faculty development. In a study at Bristol Community College in Massachusetts, a survey of most faculty before a writing center was installed found that the faculty wouldn’t allow students to revise their writing after grading, but when the college got a writing center, teachers began to insist that students revise assignments after feedback (16). Overall, the writing center is a strongly accepted Oos when it comes to the improvement of student outcomes.

In thinking about a writing center’s major questions, Cassie Book notes in her second paper on “major questions” that one thing writing centers are concerned with is writing center pedagogy. In the paper, Book notes that one major part of writing center pedagogy is that the tutor values “indirectness, avoidance of authority” in the writing center appointments. This is reiterated by Powers, who notes that one of the values of writing center tutoring is leading students to discover their own answers or solutions to their writing (40). Powers also notes that another common pedagogical technique is asking students to read their work out loud to hear error correction (42). However, while these techniques are found to be useful for native speakers, many new studies are finding that these techniques are not effective for ESL/developmental writers. “Unfortunately, many of the collaborative techniques that had been so successful with native-speaking writers appeared to fail (or work differently) when applied to ESL conferences” Powers notes (40). It is then important to shift the major question to “how do support services best help ESL/developmental students?” With this question in mind, three important questions emerge that are frequently analyzed:

- Should we train tutors to work with ESL students?

- Which techniques work for ESL students?

- Should we require ESL students to visit the writing center?

In shifting from Book’s major question towards a pedagogy for ESL/developmental writers, many authors suggest that, yes, we should train tutors to work with ESL students. Kennedy notes that most instructors and writing centers teach both native and non-native English speakers, yet have no training in helping ESL students. However, these two groups tend to have different language problems that must be also approached differently (27). In addition, Williams notes that teachers send students to the writing center to “fix” and “improve ESL writing student outcomes” when they are unable to help students themselves. Without proper training, the writing center will rely on sending students to handbooks of grammatical forms that are “frustratingly ineffective.” Without proper training in ESL writing issues, writing centers will not be useful for most non-native students.

The second question, then, takes on importance: what techniques work for ESL students? Williams recommends that for teaching of grammar, tutors should take a “systems approach,” in which they direct students to grammatical or language patterns throughout writing. For example, when a student can recognize that the “regular past tense marking with ed” is a pattern, they can project that knowledge “onto new forms” (78-9). Applied linguists generally agree that such teaching is possible on the part of the tutor (78), as long as the the tutor knows the grammar rules himself (79).

Many of the authors also suggest a more hands-on approach. While traditional writing center pedagogy asks tutors to take a generally hands-off approach, when working with ESL students, these writers prefer a tutor with more dominant behavior. Negotiating more directly with a tutor about writing changes is particularly useful, according to Williams (81-2). Powers also notes a need for increased emphasis as an informant rather than a collaborator with ESL students. A direct approach in teaching writing as an academic subject is particularly helpful (45).

Finally, the authors stress teaching tutors to help students understand the cultural differences in writing in their native language and English. For example, Powers notes that cultural ideas about writing can cause problems; therefore, teaching a native speaker that a conclusion shouldn’t contain new ideas is necessary when in their own language, this may be an accepted practice (41). Kennedy notes the same thing: students need to be taught reciprocally that what is acceptable in English writing may not be in their native language and what is acceptable in their native language may not be in English (33); therefore, teaching students the background on American culture and expectations in the classroom is important for ESL writers to fully understand what their teacher is asking for (35).

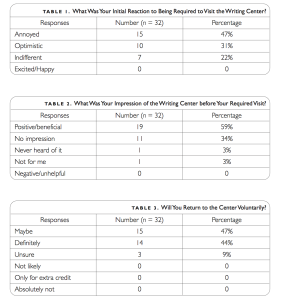

The third question, whether or not we should force ESL students to visit the writing center, is still up for debate. Many of the authors cite North’s “The Idea of a Writing Center,” and his statement that forcing students to go to the writing center is not worthwhile. However, many authors challenge this assumption. Mohamad and Boyd found that requiring students to visit the writing center for fifteen hours a semester greatly increased student writing performance. There was, first and foremost a “dramatic jump in these students’ … test scores from the initial placement test to the post-test,” and while a majority of students felt indifferent or annoyed with the requirement to visit the Writing Studio for such a great number of hours, after the course “91% of the students indicated that they would ‘definitely or maybe’ return voluntarily” (87-8). According to Gordon, making writing center visits mandatory, can “ameliorate the implications” that the writing center is a remedial service (160). In fact, in a survey of students, Clark notes that most students noted that if they were not forced to go to the writing center, they were highly unlikely to ever go; once they do go, however, they see it’s value and will continue to go (33). Gordon notes that the greatest hindrance to requiring students to use the writing center is the burden on writing center staff, yet he believes that by working with faculty, the writing center can make sure it does not get overburdened (161). Such a method will be beneficial for students.

In Gordon’s “Requiring First Year Writing Classes to Visit the Writing Center: Bad Attitudes or Positive Results,” while a majority of students required to go to the writing center initially were “annoyed,” most of them found the experience “positive/beneficial” and were “definitely” or “maybe” likely to go back. This shows that requiring visits may have more potential than suggested in North’s “The Idea of a Writing Center.”

Based on the history of ESL/developmental English, as I noted in Paper 1, frequently developmental English is one of marginalization and containment for non-native speakers of English (Kei Matsuda 641-42). However, as Cassie Book notes, with the widespread development of the writing center by the 1960s and ‘70s, particularly in response to open-admissions policies at colleges, writing centers are one step in attempting to challenge the containment and prejudice faced by developmental writers. However, Book also notes that a major problem with the history of the writing center is that little has changed since the 1980s. Little new research has emerged since then, and writing center pedagogy is perhaps a bit stuck. My research on ESL writing somewhat reiterates these findings – while writing centers are discovering problems they face in helping ESL writers, they are still struggling to develop ways to effectively help this unique group. With more research and training, writing centers will be able to not only help native speakers with the pedagogical methods they have found work best, but they will be able to shift their methods to work with diverse audiences.

After doing this research, I realized that I needed to take greater advantage of the writing center on my own campus. Each semester, I bring my first semester English students into the writing center to meet the tutors, see the center, and get a chance to ask questions. Most students do not know this service is available at all, so just getting them in the door is my typical goal. After this visit, I know that a very small percentage of students actually utilize the writing center. These are typically the most motivated students – maybe the students who would do well anyways, which potentially complicates data that suggests that students who visit the writing center do better in classes. If my personal course outcome for my students is to get them to improve writing, and according to statistics (whether my hypothesis complicates these or not), students who utilize the writing center do better, how can I better help and encourage my students to utilize the writing center?

As I mentioned in PAB #6, the writing center at NOVA is quite understaffed for a school of our size. While the writing center claims that students need only make appointments two weeks in advance, my students tell me that they cannot book even four weeks out because the center is full. When the advice of many of the writers I surveyed mentioned that requiring students to use the writing center is actually quite useful, how, when my students can’t even book individual appointments, can I get them all to see a tutor? In search of an answer, I spoke with Emily Miller, the head of the NOVA writing center. She noted that tutors are willing to set up individual appointments to come to a class and give tutoring. Yet, Dinitz and Howe note major problems with this method. When a tutor attempts to help a whole class, there is frequently “panic at the end of the class when only half of the students received tutoring” (49). The tutors in this situation frequently also find themselves too physically drained at the end of such intensive sessions to even perform their own school work up to a high standard (49).

Dinitz and Howe do propose a plausible solution that would help students get tutoring without burdening the system, and this ends up being something I could bring into my own class. They recommend bringing a tutor into the classroom to teach students how to respond to each other’s drafts, critique, and work effectively in groups (49). This way, peer review allows students to hear from three or four writers; in particular, writers who know the assignment well and are writing on the same thing (50). Then, students can go to the writing center as needed with follow-up questions (50). While I have never had a writing center tutor in my classroom to help facilitate peer review (of which I am a big believer), this method might be an interesting way to see if students find it useful. Such a technique could be grounds for further study on my part to see if bringing a tutor into my classroom for peer review leads to greater gains than the peer review I am currently using with my classes.

Ultimately, writing centers have proven their worth in the university as a system for helping improve student outcomes. While we are still investigating how to utilize them to best help ESL and developmental writers, and how to bring their services to the most possible students, these are important and worthy goals because of the great benefits possible when such services are available to students.

Works Cited

Book, Cassie. “ENGL 810 Paper #1 The History of Writing Centers as a Subdiscipline.” Cassie’s ODU Blog. Old Dominion University. 17 Sept. 2015. Web. 13 Oct. 2015.

Clark, Irene. “Leading the Horse: The Writing Center and Required Visits.” The Writing Center Journal 5.2 (1985): 31-35. Web.

Dinitz, Susan, and Diane Howe. “Writing Centers and Writing-Across-the-Curriculum: An Evolving Partnership.” The Writing Center Journal 10.1 (1989): 45-53. Web.

Gordon, Barbara Lynn. “Requiring First-Year Writing Classes to Visit the Writing Center: Bad Attitudes or Positive Results?” Teaching English at the Two Year College 36.2 (2008): 154-163. Web.

Jones, Casey. “The Relationship Between Writing Centers and Improvement in Writing Ability:An Assessment of the Literature.” Education 122.1 (2001): 3-20. Web.

Kei Matsuda, Paul. “The Myth of Linguistic Homogeneity in U.S. College Composition.” College English 68.6 (2006): 637-651. Print.

Kennedy, Barbara. “Non-Native Speakers as Students in First-Year Composition Classes With Native Speakers: How Can Writing Tutors Help?” The Writing Center Journal 13.2 (1993): 27-38. Print.

Mohamad, Mutiara and Janet Boyd. “Realizing Distributed Gains: How Collaboration with Support Services Transformed a Basic Writing Program for International Students.” Journal of Basic Writing 29.1 (2010): 78-98. Print.

Powers, Judith. “Rethinking Writing Center Conferencing Strategies for the ESL Writer.” The Writing Center Journal 13.2 (1993): 39-48. Web.

Williams, Jessica. “Undergraduate Second Language Writers in the Writing Center.” Journal of Basic Writing 21.2 (2002): 73-91. Print.