The top image is Stanford University’s graduating class in 1895. The bottom is a photo from graduation in 2015. The differences in race and culture represented in these images highlights the changing face of college education in our country and the fears and missteps made in the addressing of this major educational issue. [http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~npmelton/stan95.jpg https://commencement.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/styles/6-col-banner/public/students_6col_0.jpg?itok=Eggs_Tse]

Harvard, from which the first year writing course began, also pioneered the writing placement exam, which functioned as a way to judge the use of “correct” English. Though they were one of the first colleges to use such exams, by the second part of the nineteenth century, with an influx of immigrant students coming to study at research universities, many other schools began to require language exams for entry to the university, and they became a site of linguistic containment and discrimination (Kei Matsuda 641-42). Essentially, these exams existed and functioned to make it appear that “language differences could be effectively removed from mainstream composition courses” (642).

Along with these exams came remediation. Second-language speakers, particularly Asian students, from Ivy League schools, to research universities, to historically black colleges and universities, were being sent to remedial language schools until they were deemed ready to return to the college to study (Kei Matsuda 644). As Horner and Trimbur note, the effort to keep these students out of the mainstream courses was due to the fear that foreign students were a “threat to the culture, economy, and physical environment of the academy” (609).

Despite the efforts to contain these students in other schools or classes, after World War II, most schools began to offer English composition courses especially for ESL students (Kei Matsuda 647). The exigencies for the emergence of these ESL composition classes was the huge number of foreign students pouring into the U.S. to study. While the number of international students has grown and then subsequently shrunk since the twentieth century, at a given time, approximately a half million foreign students are in U.S. colleges studying (640). With this number, schools could no longer deny these students an opportunity to be educated both in developmental and mainstream courses alongside native speakers of English.

The relationship of ESL/developmental English to the rest of the university depends upon the school itself. While Kei Matsuda notes that some schools offer fully contained classes with just ESL speakers, others mix classes between native/nonnative to make them more “international” for both native speaking and nonnative speaking students (647).

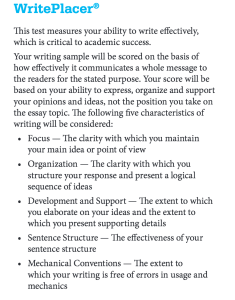

While these readings have done a good job getting at where, when, and why the university started ESL or developmental English courses, it does not quite articulate how they are related to the rest of the university system. Kei Matsuda and Horner and Trimbur note how closely these courses (which are typically tied to the English department) rely upon placement tests. It is through these tests that the English department is tied heavily to the rest of the college because the placement practices are college-wide and inescapable by any incoming student. For example, at Northern Virginia Community College, all ESL students are required to take the ACCUPLACER exam. This exam places students either into ESL courses, or, if they “test out” of ESL, into a developmental English class. Because all students run through the testing center, and because NOVA enrolls approximately 2000 international students annually, the role of ESL and composition course are heavily connected to all other parts of the college. Students must complete developmental English sequences before moving on to other classes (in fact, at NOVA it is not recommended that students take any courses outside of ESL until they have reached the highest level, Level 5), and there is a strong recommendation on the part of the college that students must master English before they will be successful in many other courses outside of the English department.

One interesting note about the Accuplacer is that ESL students are evaluated in a similar way to the placement test of non-ESL students. If these tests are designed to measure relatively the same thing, why the different tests? Is this test in some way segregating ESL students when they might be served by the general college placement tests?

These placement practices represent possible discriminatory practices on the part of the college or individual teachers; however, there is no simple solution for this problem. As Horner and Trimbur note, they “are not quarreling with the fact that writing instruction in college composition courses takes place in English” (593); in 2015, English in the U.S. college is a certainty and a reality that we must deal with. However, a balance must be made between disenfranchising students from deserved education and making sure they have enough English to be successful in an American composition class.

As I mentioned in my PAB posts – the question I keep asking is “what do we do?” We know that English is a necessity, but we don’t want to inhibit students from success and we certainly don’t want to discriminate against them. The reading by Dell Hymes this week shed some insight on one possible solution. As Hymes describes a definition of communicative competence, I was struck by the definition of what makes language communicative. Hymes notes that communication is not only about functional competence – being able to use the words in a way that are understandable (57), but also an ability to both know what to say and how to say it (62). If this is the way we might judge language, in a sense, all of our students are ESL students. While those who are not “American” might make some grammatical mistakes and misuse words (a functional meaning), all of my students struggle with a cultural competence of language – saying something the right way that gets the intended message across to the audience. My point, then, is that if I read Hymes in a way that is particularly relevant to me as an English/ESL teacher, as long as these nonnative students are competent to communicate functionally, they exist on a nearly even playing field with their native classmates.

This breakthrough actually fits quite well with what I’ve discovered when I teach a developmental class followed by a “regular” section of writing. All of my students are building their communicative competence, and they often help each other along in the classroom setting. Typically, the “lower-level” students are carried up by the higher-level students and all of the students in the class do a little bit better. When I have a class of all ESL or developmental students, this progress is still there, but slightly more stagnant. While I could digress into a long analysis of the Zone of Proximal Development here, instead I believe that Hymes helped me to realize that a possible solution to these issues is to mix these students into regular classes instead of having them segregated, as all of the students will help each other with their cultural competence issues. Any extra language help that these students truly do need (to improve their functional communication) could be done in a smaller group session with me where I could focus on the students more individually. This would serve not only to desegregate these classes, but would help improve the communication of all of these students.

My next steps are to figure out how within the next several years I might use this information to consider how to make policy changes at NOVA, how to best serve nonnative students, and how to make their experience easier while not losing sight of their unique challenges.

Works Cited

Horner, Bruce and John Trimbur. “English Only and U.S. Composition.” College Composition and Communication 53.4 (2002): 594-630. Print.

Hymes, Dell. “On Communicative Competence.” Research Planning Conference on Language and Development Among Disadvantaged Children. Yeshiva University. Frankfurt Graduate School. 7 June 1966. Address.

Kei Matsuda, Paul. “The Myth of Linguistic Homogeneity in U.S. College Composition.” College English 68.6 (2006): 637-651. Print.