In this article, Katherine Mason provides a definition of cooperative learning for ESL and developmental English learners that encompasses both face-to-face teaching and online teaching as a way to improve student outcomes. Mason notes that many ESL students come into college with a fear of speaking English in front of their classmates when it isn’t their native language. This occurs for two reasons. One is that in their culture, educational emphasis is placed on listening rather than speaking. The other is that when students are set up to do group work and must be actively engaged, they often feel that their classmates (particularly those who are not ESL speakers) have better and smarter ideas and they fear looking stupid or less educated (52).

Mason notes that despite this fear, often, setting up a space in which students feel comfortable doing cooperative learning, which she defines as

“face-to-face or online” communication that “promotes a sense of community among students” and includes an emphasis on “interdependence, individual accountability, equal participation, and simultaneous interaction,” promotes greater learning and more comfort in speaking English and sharing their ideas (53).

She notes that cooperative learning has the power to increase linguistic diversity in students more than a traditional lecture. She does warn, however, that a teacher must create modeling and feedback for students so they can successfully work cooperatively (53).

Some of Mason’s recommended activities include both classroom and online work. For classroom work, she recommends asking students to write a stance on an issue and some counterarguments. When sharing their arguments with teams of four or five, other teammates may suggest other possible counterarguments, which helps students develop ideas for writing and practices spoken English (54). For online cooperative learning she suggests asking students to put paper outlines on a Blackboard forum where a small group will read and respond to each other’s proposals providing group critiques (55). Mason has found that such group work is better than a teacher giving feedback, as students often think of feedback that even the teacher wouldn’t have thought about and that students benefit not only from receiving but from giving feedback (55). The students also report that they become more careful about their own drafts when they realize the criticisms they see in other students’ drafts (56).

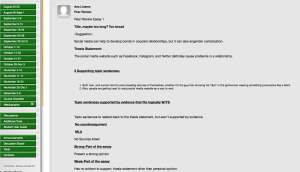

Here is an example of a similar Blackboard peer review I did in my own class. Students submit their thesis statements and evidence to the board and must respond to at least two of their classmate’s work.

Finally, Mason notes that teachers shouldn’t be too worried about students who are initially quiet or reluctant to participate. She believes that many quiet students are gaining “peripheral participation” and absorbing ideas by listening and that as the semester goes on, they are more likely to become active participants when they learn that speaking up is good practice to think critically and an opportunity to share their opinion (54). Ultimately, this shows the true value of cooperative learning:

“The very act of genuinely communicating with peers from diverse backgrounds through cooperative team-building structures alleviates fears, breaks down stereotypes, and promotes relationship building among students” (57).

Students who learn cooperatively become better writers, students, and more culturally-aware citizens.

Something that struck me as I read this was a reminder of Dell Hymes’ definition of communicative competence. Communicative competence in a cultural aspect as Hymes describes it is when someone learns how to speak language effectively to a particular culture to accomplish their purpose. When I have such a linguistically diverse class (particularly for my ESL English classes), getting students to the place that Mason describes, where students feel comfortable enough for their voices to be heard and are able to be understood is always one of my main goals. My goal is not for students to leave my class speaking standard English, but to be able to comfortably communicate in a college classroom with peers and to take some new knowledge away from that. The question I must then ask is, how do I speed up the process of getting those uncomfortable students to speak? It seems that Mason would argue the more they speak, the more quickly they will improve, but often getting my quietest students to speak is like pulling teeth. However, such cooperative learning would, as both Hymes and Mason would argue, make students improve more rapidly. How to speed up their communicative competence is something I need to consider further.

Lev Vygotsky, the father of a developmental theory of education, changed everything when he introduced the ZPD, which has spurred decades of thinking on cooperative learning in the classroom.

In addition to Hymes, Mason’s definition fits very well again with a developmental theory of learning. Vygotsky’s ZPD helps explain Mason’s success. What she is describing here – students being “equal partners” in learning and being required to participate with their group gives them not only the feedback of their peers to make themselves better, but in giving feedback, they gain the confidence in their abilities and thoughts that eventually will allow them to move to new levels of competence as learners (Vygotsky 86). When Mason notes that often times students will provide feedback that she has never considered before is something I frequently encounter. While I am happy to sit down with students in conferences to discuss their writing, I am still only that – one perspective. By allowing students opportunities for conferring with peers as well, they gain new ideas and I gain new ideas also. This form of cooperative learning benefits both the students and the teacher alike. However, the questions that arise out of this yet again has to do with how I pair students for such work. Is it best to allow students to pick their own groups, or should I form them myself specifically putting weaker and stronger students together? If I do that, do the stronger students only benefit from helping others but not get a perceived benefit on their own? I frequently remember my own peer review days when I felt I got nothing worthwhile out of feedback. In what ways do teachers respond to the problems of such drastic differences in abilities and help cooperative learning improve all students? I haven’t figured out the most ideal solutions to these problems in my own class yet.

Works Cited

Hymes, Dell. “On Communicative Competence.” Research Planning Conference on Language and Development Among Disadvantaged Children. Yeshiva University. Frankfurt Graduate School. 7 June 1966. Address.

Mason, Katherine. “Cooperative Learning and Second Language Acquisition in First-Year Composition: Opportunities for Authentic Communication among English Language Learners.” Teaching English in the Two Year College 34.1 (2006): 52-58. Web.

Vygotsky, Lev. Mind in Society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1978. Print.